Offline Evaluation Is Dead: How Consumer AI Learns from Millions of Real User Decisions

Offline Evaluation Is Dead: How Consumer AI Learns from Millions of Real User Decisions

Once consumer AI products reach scale, offline evaluation isn't just "not good enough"—it's irrelevant to production decisions. This conclusion comes from running systems at tens of millions of users, processing billions of conversations and behavioral signals every month.

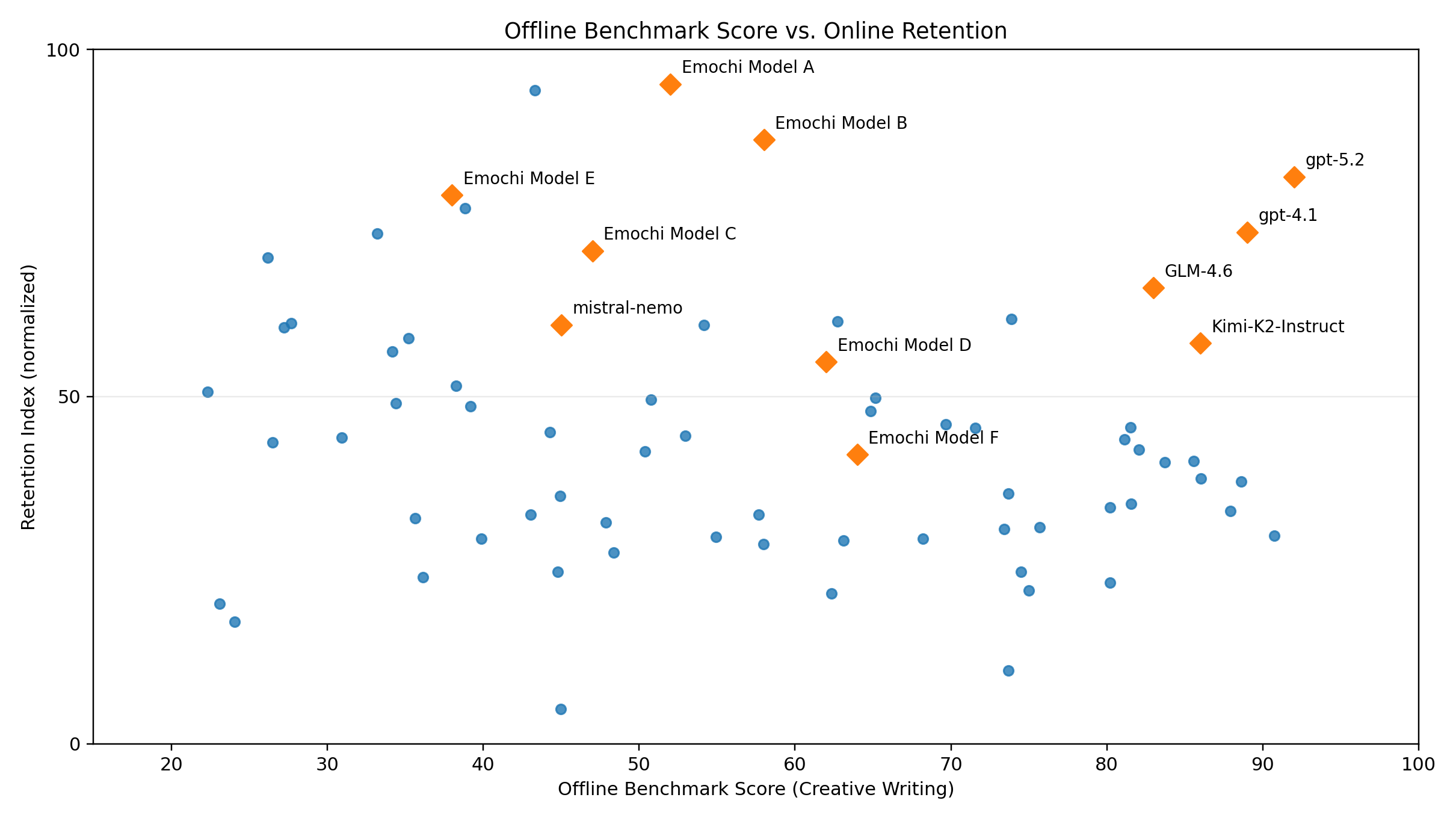

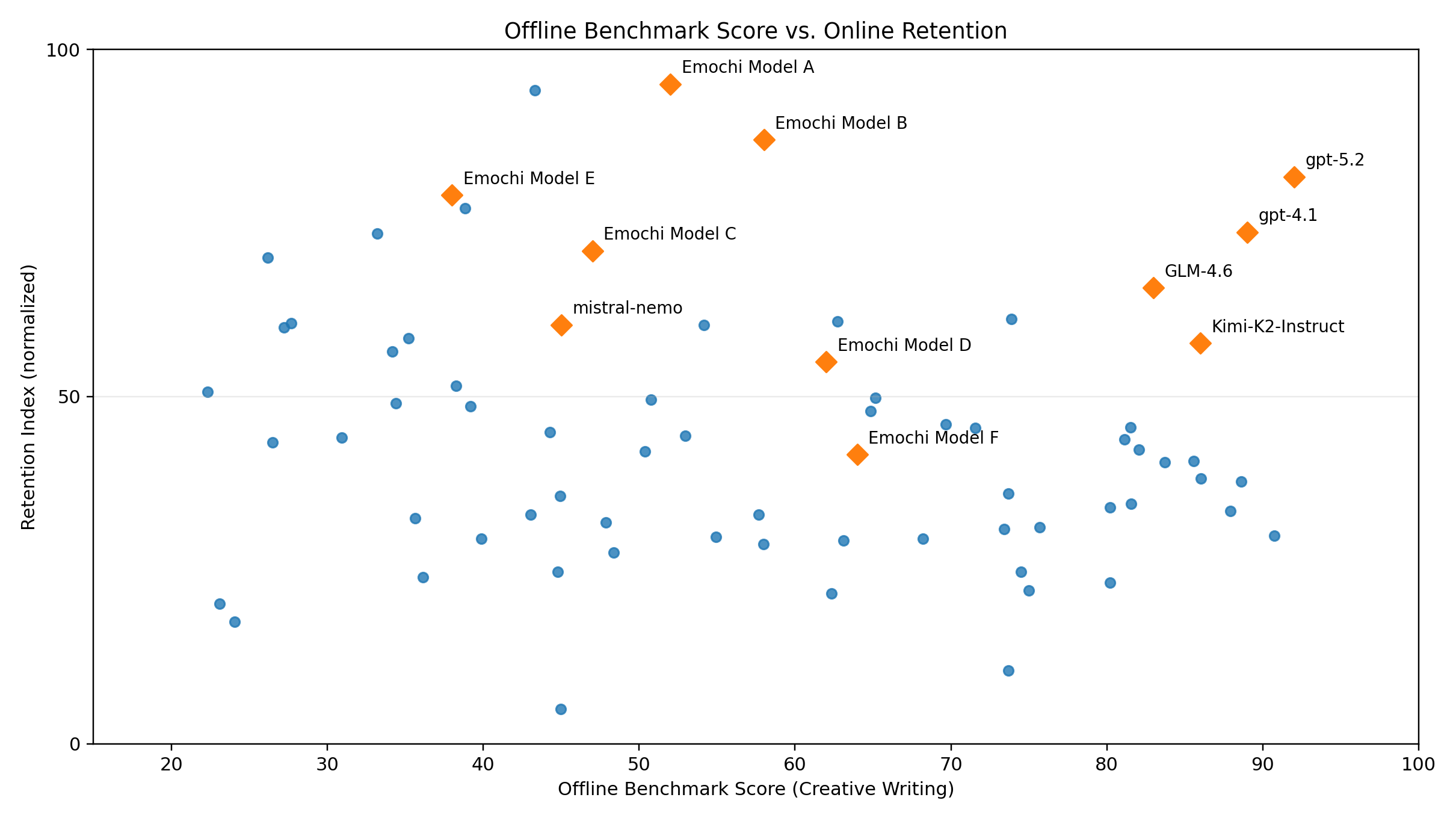

We've seen this pattern repeatedly in real user environments: models that top public creative writing benchmarks often underperform in actual usage. Meanwhile, models with unremarkable offline scores consistently drive better retention, deeper conversations, and higher continuation rates. In some cases, multiple benchmark top-5 models get outperformed by a model ranked significantly lower offline.

This isn't anecdotal. It's structural.

Offline benchmarks solve for discrete, bounded problems—tasks with clear boundaries and correct answers. Consumer AI faces something fundamentally different: continuous content consumption experiences that span multiple conversation turns and contexts. In entertainment and creative writing, there's no objective ground truth, only preference. Benchmarks designed for discrete tasks can produce scores, but those scores don't reliably map to how people actually behave at scale.

Offline evaluation is failing—not because benchmarks are poorly designed, but because they're fundamentally misaligned with consumer AI.

As model costs continue dropping in 2026 and user expectations mature rapidly, the real product edge won't be who has the best demo—it will be who can iterate faster, and who can make the right call on which model deserves to stay. In this context, evaluation is no longer a supporting system—it's the core bottleneck determining product ceiling. Yet in consumer AI, there's still no mature, scalable evaluation methodology.

The problem isn't whether model responses are "accurate." The problem is defining what success even means.

The Fundamental Mismatch

At its core, an offline benchmark is a set of artificially constructed tasks: tasks defined by humans, graders designed by humans (or LLMs), success criteria locked in before experiments begin. This might work in constrained scenarios. But in large-scale consumer AI, pre-defining success is inherently unsustainable.

Content products learned this lesson years ago. As Eugene Wei points out in his analysis of TikTok, the system isn't trying to decide whether content is "good." It continuously observes behavior, infers each user's preference distribution, and ranks accordingly. In that setup, behavior is the only signal that scales, and any evaluation framework that tries to define "good content" upfront collapses in front of real users.

In consumer apps, user behavior is the only ground truth.

This is exactly why offline eval systematically fails in consumer contexts: it optimizes for "answers that look correct," while users reward "experiences that feel right." When evaluation systems decouple from real user behavior, they can produce scores, but those scores can't support any critical decisions.

We saw a direct example on Emochi (our creative fiction product): among models ranked top-5 on a public Creative Writing benchmark, several showed lower user retention than models ranked much lower offline. That's not a one-off. It's a warning: when "scoring criteria" and "user preferences" aren't the same thing, offline scores become an illusion.

Offline Benchmark Score vs. Online Retention

For consumer AI, any evaluation system that can't be driven by real user online behavior isn't "incomplete"—it's irrelevant. Scalable online evaluation infrastructure based on real user feedback is no longer optional. It's the only path forward.

Evaluation Only Scales When It's Closed-Loop

In consumer AI, model evaluation is no longer a standalone step—it's a continuously running closed-loop feedback system. Models get deployed, used, compared, filtered, trained, then return to real user environments for validation. The core of this loop: all critical evaluation signals come from real user online behavior.

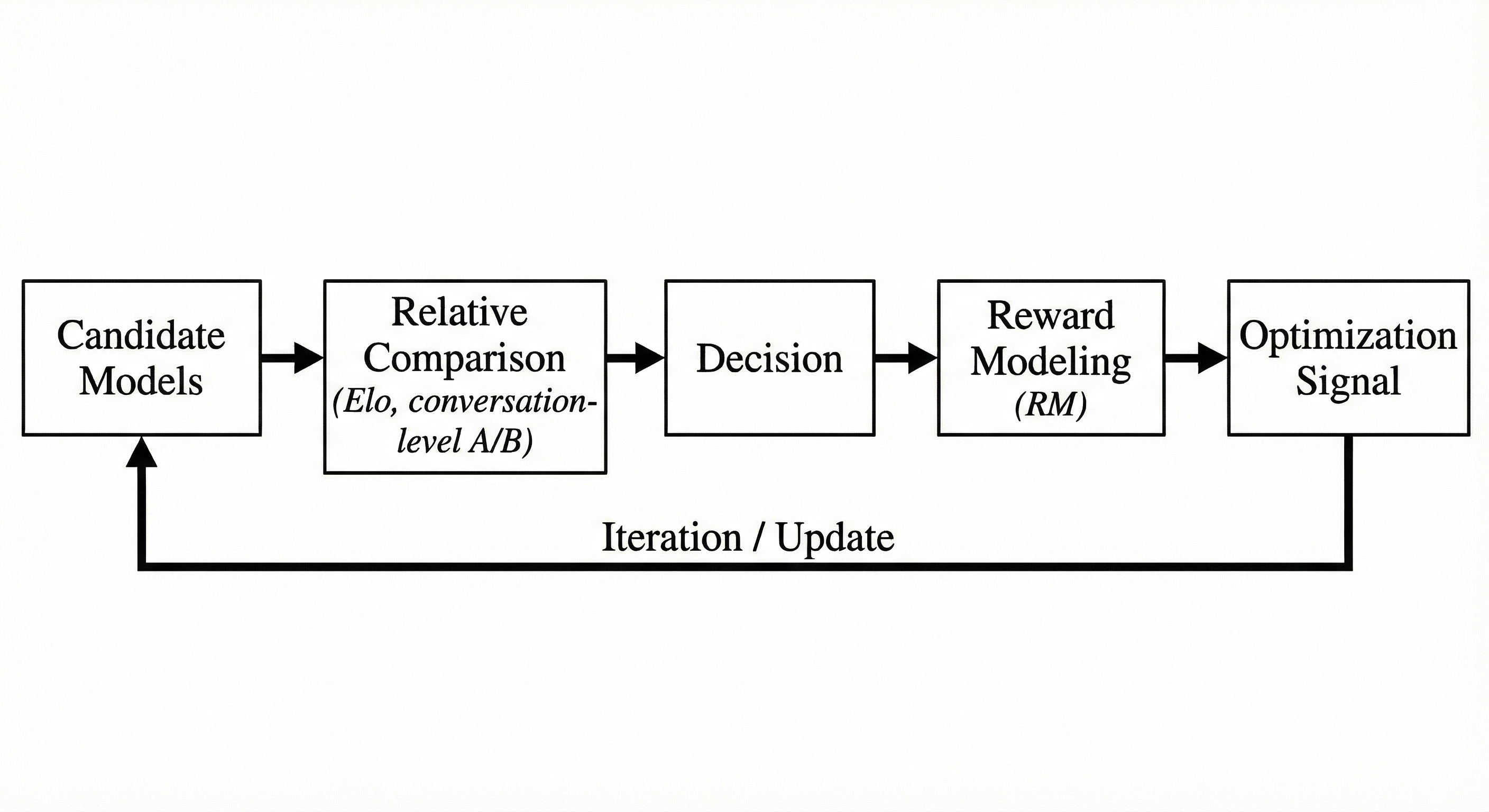

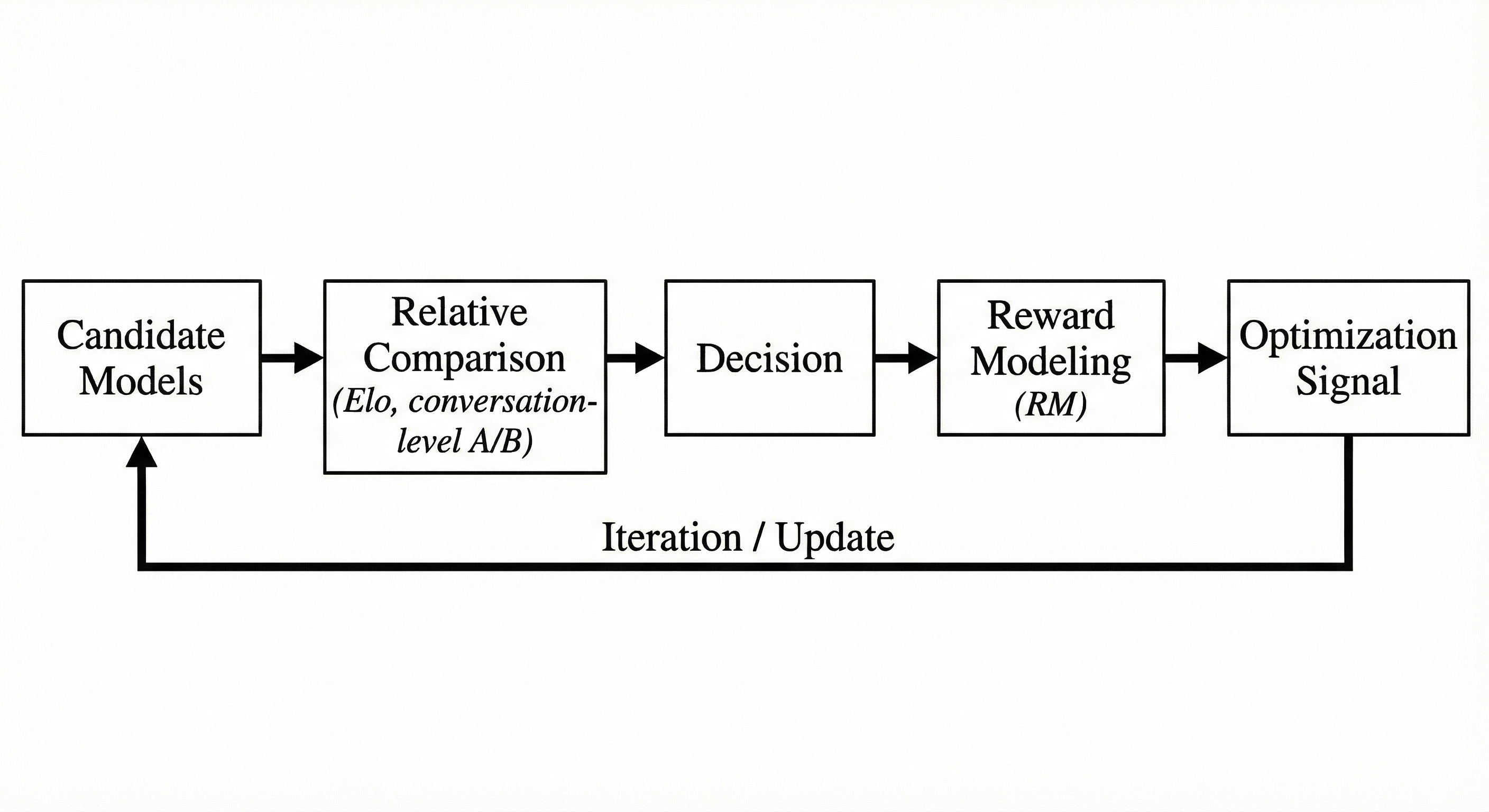

In production, the loop converges to something like this:

models → relative comparison (Elo, conversation-level A/B) →

decision → reward modeling (RM) → signal → models

Closed-Loop Evaluation System

Everything runs on real user data. Relative comparison continuously harvests preference signals. Those signals become operational decisions—what to ramp, keep, or cut. And the same feedback is modeled into product-specific rewards that drive the next training cycle.

Within this system, Elo, conversation-level A/B, and RM aren't parallel evaluation tools—they're system components operating at different layers, solving different problems:

Elo solves for scale. Conversation-level A/B solves for evaluation unit. RM solves for how evaluation enters training.

When these components unify within the same closed loop, evaluation stops being a step that "validates whether a model is good." It becomes infrastructure driving continuous model evolution. Any evaluation system not built on real user behavior will ultimately optimize for a product that no longer exists.

Ranking Models by User Preference, Not Static Scores

At this stage, the primary constraint on evaluation systems isn't statistical precision—it's throughput and time-to-decision.

Traditional A/B testing assumes three premises: stable evaluation targets, sufficiently long experiment windows, and slowly changing model sets. In real consumer AI production environments, nearly all these premises fail. New models might join on a daily or even hourly basis. Before a traditional A/B experiment converges, candidate models are often already obsolete.

Relative ranking systems (like Elo, or more precisely, TrueSkill) happen to fit these constraints. They're designed to tolerate noise, incomplete matchups, and continuously changing opponents—characteristics highly aligned with online traffic scenarios.

We don't use Elo to find a "globally optimal model." We use it to solve a more engineering-focused problem: given current traffic and time windows, which models can be confidently eliminated.

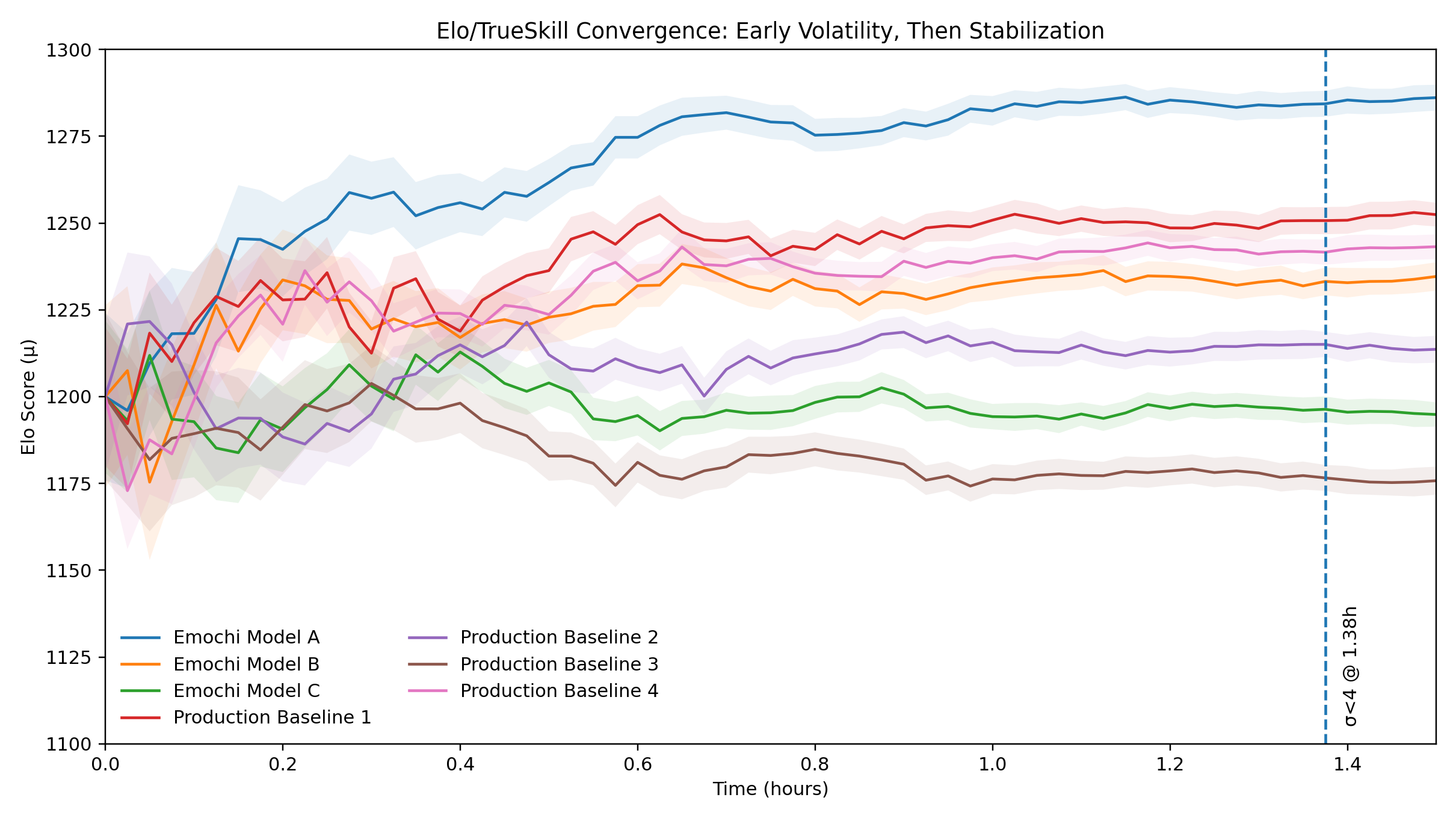

More importantly, we don't treat ranking results as "absolute scores"—we treat them as online estimates with uncertainty. TrueSkill uses (μ, σ) to explicitly express "current strength" and "confidence level." This allows the system to pursue stable relative ordering even when noise is unavoidable and preferences continuously drift—rather than chasing a seemingly precise but production-unreliable single-point score.

To keep ranking controllable over long horizons, we run it like infrastructure, not a one-off experiment:

- Basic sample-quality filtering (e.g., removing unstable matchups with too few turns)

- Robustness checks via merging and shuffling to reduce sensitivity to matchup order

- A stable set of reference models as anchors, to stabilize scale, cold-start new candidates, and reduce drift as the pool churns

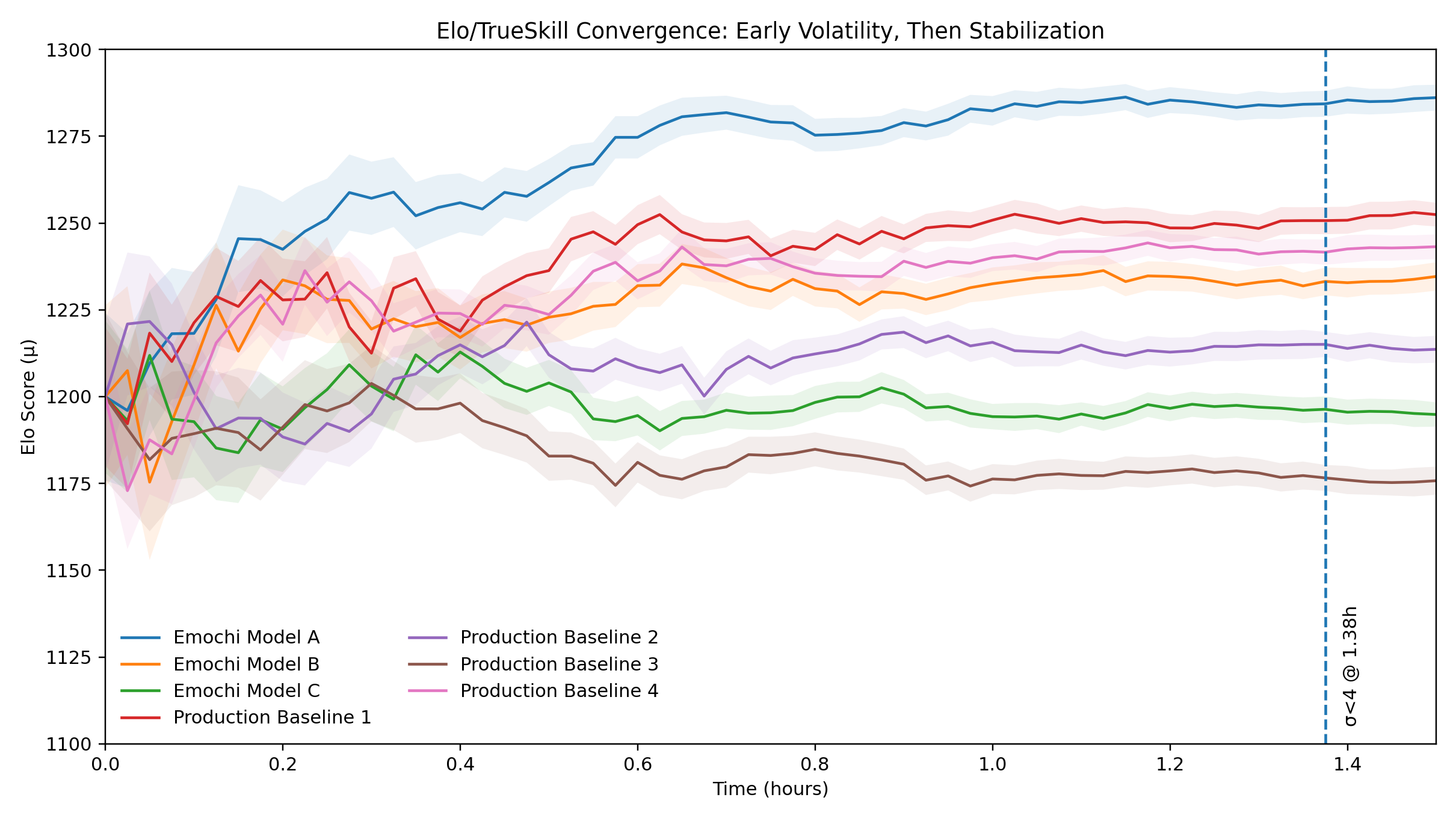

Elo/TrueSkill is always a filter, never a final truth. Its job is to cheaply rule out bad bets fast, and reserve heavier evaluation bandwidth for the candidates that survive. In our current traffic, we can typically eliminate obviously mismatched models within hours, using hundreds of thousands of comparison samples—then focus deeper A/B and RM resources on the top pool.

Elo/TrueSkill Convergence: Early Volatility, Then Stabilization

User-Level A/B Fails in High-Velocity AI Systems

In consumer AI products, traditional user-id-based A/B testing is systematically failing. The root cause isn't statistical methods—it's choosing the wrong evaluation unit.

Users aren't the minimum causal unit in large model interactions.

In classic internet products, user-level randomization makes sense: the product logic is stable over the experiment window, and behavior shifts can be attributed to the treatment. In consumer AI, that premise breaks. User-model interaction is highly context-dependent, path-dependent, and nonlinear. The same user's behavior across different conversations can vary more than different users' behavior within the same conversation type.

What actually carries model capability differences isn't the user. It's the conversation.

If evaluation still uses user-id as the unit, model differences get drowned out by users' own strong noise, usage habits, and historical preferences. Experiment results struggle to converge, can't be explained, and can't support rapid decisions. In practice, we've repeatedly observed: when model iteration frequency increases and candidate model count grows, user-level A/B tests often achieve statistical "significance" but provide zero guidance on product metrics.

This isn't an experiment design problem. It's a misalignment between evaluation target and decision objective.

So we moved the unit from user to conversation. Each complete conversation becomes one evaluation sample. Within that boundary, the model owns the full context and generation process, and user behaviors—continue, interrupt, retry, abandon, dwell time, depth—are attributed to the model's performance in that specific interaction. At our scale, we generate tens of millions of conversation samples daily, which makes conversation-level attribution both cleaner and faster to converge.

This shift brings three critical changes:

First, causal attribution becomes clear. The model's impact on user experience is no longer diluted across conversations and time—it's constrained within a clear context boundary.

Second, experiment convergence speed significantly improves. Since conversation-level sample noise is far lower than user-level, relative differences between models can be identified within shorter time windows—crucial for high-frequency model iteration.

Third, evaluation results align better with real product decisions. Products don't care about "which model is better for some user in the long-term average"—they care about "in the current usage scenario, which model is more likely to make a conversation succeed."

Conversation-level A/B isn't an optimization of traditional A/B—it's a paradigm shift in evaluation. It abandons modeling of users' long-term behavior in exchange for high-resolution judgment on single interaction quality. This tradeoff isn't free, but in consumer AI scenarios, it better aligns with the system's true objective function.

In high-concurrency, fast-iteration production environments, model success isn't determined by "whether users generally prefer it more"—it's determined by how many specific conversations it gets immediately chosen or abandoned in by real users.

Limitations and Applicability

Conversation-level A/B isn't a universally applicable evaluation approach.

First, when conversation value primarily manifests in cross-session long-term relationships or emotional accumulation rather than within-session immediate experience, using conversation as the evaluation unit might underestimate the model's true impact. For example, in scenarios where companionship, role consistency, or long-term interaction stickiness are core goals, whether users continuously return and form stable usage habits often matters more than immediate feedback in single conversations.

In such cases, within-conversation behavioral signals (continuation, dwell time, selection) remain valuable, but they can't fully characterize user value over longer timescales.

Second, when products are in early stages with unstable conversation distributions, or user scale is insufficient for adequate sampling, conversation-level signals can easily be dominated by extreme samples. Relying on this evaluation approach too early might amplify short-term noise rather than true preferences.

Additionally, conversation-level A/B intentionally abandons modeling of long-term user behavior consistency. This tradeoff exchanges faster convergence speed and clearer causal attribution, but also means it's unsuitable for answering questions like "will a specific user prefer a certain model long-term."

The system design premise is: in consumer AI scenarios, whether a model is worth continued iteration depends on whether it consistently gets chosen by users in large numbers of specific conversations.

Conversation-level A/B isn't a complete replacement for traditional user-level A/B—it's a specialized evaluation primitive for high-concurrency, fast-iteration model environments. It sacrifices some long-term behavior modeling capability in exchange for sustainable decision efficiency in real production systems.

Turning User Behavior into a Learning Signal

If evaluation can only tell us "which model is better" but can't influence model evolution itself, it ultimately remains just a post-hoc explanation system, not part of the production system.

In consumer AI, iteration speed sets the ceiling for what evaluation is worth. The loop only becomes real when evaluation signals flow back into training continuously and reliably—so model selection, optimization, and real user preference actually close.

This feedback pipeline accumulates hundreds of millions of implicit labels and large volumes of pairwise preference samples daily, giving reward signals the density and coverage needed for sustainable training.

This is exactly RM's (Reward Model) role in the entire system.

Unlike generic reward models, Emochi's RM doesn't start from abstract preferences or human annotations—it's built directly on real user behavior. The system doesn't assume users will explicitly tell us "what a good model is." It assumes users will continuously reveal true preferences through behavior.

These behavioral signals include but aren't limited to: whether users continue conversations, next-turn query length, dwell time on model responses, explicit like/dislike, and actual choices during model matchups. These signals may be noisy in single interactions, but when aggregated at scale, they're repeatedly validated as highly correlated with long-term retention and engagement.

The key is that these signals aren't used in isolation. RM's function is to unify user feedback from different evaluation system layers into a learnable reward space, enabling model training to directly align with real product goals rather than some static offline metric.

RM isn't a one-time trained model—it's a continuously calibrated system. As user behavior distributions, product forms, and model capabilities change, reward signals themselves will drift. The system design goal isn't to eliminate this drift—it's to maintain long-term correlation between rewards and real user value under inevitable drift.

When evaluation signals, model decisions, and training feedback unify in the same closed loop, model optimization no longer depends on offline assumptions—it's directly constrained by real user behavior. This enables the entire system to continuously self-correct at scale rather than relying on periodic manual calibration.

In this sense, RM isn't an auxiliary module of the evaluation system—it's the final piece that makes consumer-scale online evaluation a "platform": it moves evaluation beyond the selection layer into the driving layer of model evolution.

This closed loop didn't start from theoretical derivation. It gradually took shape in Emochi's real user environment, accompanying growth in model scale, traffic, and product complexity. Through long-term operation, we repeatedly observed: when evaluation decisions are truly handed over to user behavior, the correlation between offline scores and core business metrics naturally recedes to secondary importance.

Trade-offs and Failure Modes

This scalable online feedback loop wasn't designed to solve all evaluation problems. Its goal is very specific, which means it makes clear trade-offs.

First, this infrastructure isn't suitable for all product stages. When product scale is still small (e.g., DAU < 50k), user behavior signals are too sparse and noisy to support stable online ranking and decisions. In such cases, human evaluation or offline analysis may still be more efficient paths. But once products cross this scale threshold, continuing to rely on offline evaluation is no longer the "safe choice"—it's outdated system design. For AI systems running in real user environments, if evaluation signals don't come from real user behavior, they will inevitably systematically diverge from product goals.

Second, this isn't an evaluation system for answering "how good is a model in absolute terms." The system doesn't try to produce cross-time, cross-scenario, reproducible absolute scores, nor does it pursue one-to-one alignment with traditional benchmarks. The only question it cares about: given current users, current distribution, current product form, which models deserve continued scaling and evolution.

Third, this system doesn't assume user feedback is clean, stable, or interpretable. On the contrary, it accepts real-world constraints from the start: user behavior is noisy, preferences drift, and product forms themselves continuously change. The system design goal isn't to eliminate these uncertainties—it's to continuously reduce decision risk when uncertainty is unavoidable.

Finally, this isn't a "one-time evaluation" solution. It can't provide definitive conclusions before models enter real usage scenarios, nor can it replace offline analysis during research stages. Its premise is that models have already been deployed, already used by real users, and evaluation itself needs to become part of product and training workflows.

Precisely because these boundaries exist, this system can operate long-term at real consumer AI scale. It abandons pursuit of "static truth" in exchange for reliable support for "continuous decisions." It abandons illusions of perfect evaluation in exchange for a production-grade platform capable of continuous self-correction.

This is what we've built:

Not an evaluation tool, but feedback infrastructure that can evolve alongside models and products.

在消费级 AI 产品达到一定规模之后,offline evaluation 并不是"不够好",而是已经在生产环境中失去决策意义。这一结论来自我们在千万级用户规模下的线上观察, 系统每月处理数 billion 级对话与行为反馈。

我们在真实用户环境中反复观察到:在公开创作类 benchmark 上排名靠前的模型,在实际用户使用中往往表现平平;而一些 offline 得分并不突出的模型,却能显著提升用户的留存、对话深度与继续率。在某些情况下,多个 benchmark Top-5 的模型,都会被一个 offline 排名明显靠后的模型稳定击败。

这不是偶发案例,而是结构性信号。

Offline benchmark 解决的是单一、离散的问题:任务边界清晰、存在标答。而 Consumer AI 面对的是连续性的内容消费体验——跨多轮对话、跨情境的整体感受。在娱乐与创作场景中,没有客观正确答案,只有用户偏好。因此,擅长评估离散任务的 benchmark,无法衡量也无法预测大规模用户的连续内容消费体验;它可以产生分数,但这些分数与真实用户行为之间并不存在稳定关系。

Offline evaluation 正在失效——不是因为 benchmark 设计得不够好,而是因为它们在根本上就不再适用于 Consumer AI。

即便是 Anthropic 在《Demystifying evals for AI agents》中,也尚未真正采用基于真实用户行为的 online evaluation。这恰恰说明:即使在最前沿的 AI 实验室中,评估范式依然停留在"局部、离散、事前定义成功标准"的阶段,而非面向大规模用户连续体验的在线闭环。这不是个别团队的问题,而是整个行业尚未跨过的范式门槛。

2026 年模型成本将持续下降,用户心智快速成熟,产品之间真正的差距,体现在谁能更快迭代、谁能更准确地判断"哪个模型应该被留下"。在这样的背景下,评估不再是辅助系统,而是决定产品上限的核心瓶颈——但在 C 端,至今仍然没有一套真正成熟、可规模化的评估方法论。

问题并不在于模型的回复"准不准",而在于什么才算成功。

Offline benchmark 的本质,是一套人为构造的任务:任务由人定义,grader 由人(或 LLM)设计,成功标准在实验开始前就已经被写死。这在受限场景中或许有效,但在大规模 Consumer AI 中,"事前定义成功"这件事本身,就是不可持续的。

这一点在内容型产品中早已有清晰验证。正如 Eugene Wei 在分析 TikTok 推荐系统时所指出的:系统并不是在理解内容"好不好",而是在通过持续观察用户行为,反向推断每个用户的偏好分布,并据此完成排序与分发。在这种机制下,行为本身就是唯一可规模化的信号,而任何试图事前定义"什么是好内容"的评估框架,都会在真实用户面前失效。

在 C 端 App 的环境下,用户的行为才是真正的 ground truth。

这正是 offline eval 在 C 端系统性失效的原因:它优化的是"看起来正确的答案",而用户奖励的,是"感觉正确的体验"。当评估体系与真实用户行为脱钩时,它可以产生分数,却无法支撑任何关键决策。

我们在 Emochi(创意小说场景)上看到一个非常直接的例子:在某个公开的 Creative Writing benchmark 排名前五的模型里,有多个模型上线后的用户留存明显低于一个 benchmark 排名远靠后的模型(例如 mistral-nemo)。这不是个例,而是一个信号:当"评分标准"与"用户偏好"不是同一个东西时,离线分数就会变成一种错觉。

离线 Benchmark 分数 vs. 在线留存率

对于 Consumer AI 来说,一套无法由真实用户在线行为驱动的评估体系,并不是"不完整",而是不相关。可规模化的、基于真实用户反馈的 online evaluation infrastructure,不再是可选项——而是唯一的出路。

Evaluation Only Scales When It Is Closed-Loop

在 Consumer AI 场景下,模型评估不再是一个独立步骤,而是一条持续运行的闭环反馈系统。模型被部署、被使用、被比较、被筛选、被训练,最终又重新回到真实用户环境中接受验证。这条闭环的核心在于:所有关键评估信号,都来自真实用户的在线行为。

在我们的生产环境中,这一机制会稳定收敛为如下循环:

models → relative comparison (Elo、conversation-level A/B) →

decision → reward modeling (RM) → signal → models

闭环评估系统

这条链路完全运行在真实用户数据之上,通过相对比较机制持续收集用户偏好信号;这些信号被聚合为可执行的模型决策,用于决定哪些模型应该被放量、保留或淘汰;同时,这些真实反馈又被进一步建模为面向产品场景的奖励信号,反向驱动下一轮模型训练与迭代。

在这个系统中,Elo、conversation-level A/B 和 RM 并不是并列的评估工具,而是处在不同层级、解决不同问题的系统组件:

- Elo 解决规模问题

- conversation-level A/B 解决评估单位问题

- RM 解决评估如何进入训练的问题

当这些组件被统一在同一条闭环中时,evaluation 不再是"验证模型好坏"的步骤,而成为驱动模型持续演化的基础设施。任何没有建立在真实用户行为之上的评估系统,最终都会优化一个已经不存在的产品。

Ranking Models by User Preference, Not by Static Scores

在这个阶段,评估系统面临的首要约束并不是统计精度,而是吞吐量与收敛速度。

传统 A/B 测试隐含了三个前提:评估对象稳定、实验窗口足够长、模型集合变化缓慢。但在真实的消费级 AI 生产环境中,这些前提几乎全部失效——新模型可能以天甚至小时为单位加入,而在一个传统 A/B 实验尚未收敛之前,候选模型往往已经过期。

相对排序系统(如 Elo,更准确地说是 TrueSkill)恰好适配了这种约束条件。它们被设计用于容忍噪声、不完整对战以及对手持续变化的环境,这些特性与线上流量场景高度一致。

因此,我们并不试图用 Elo 找到"全局最优模型",而是用它解决一个更工程化的问题:在当前流量与时间窗口下,哪些模型已经可以被明确排除。

更关键的是,我们并不把排序结果当作"绝对分数",而是把它当作一个带不确定性的在线估计:TrueSkill 用(μ, σ)显式表达"当前实力"与"置信度"。这使得系统可以在噪声不可避免、偏好持续漂移的前提下,仍然追求稳定的相对顺序——而不是追求一个看似精确、但在生产中并不可靠的单点分数。

为了让这套排序在长期运行中保持可控,我们把它当作基础设施来维护,而不是一次性实验:

- 对样本质量做基础过滤(例如剔除对战轮次过少导致的不稳定样本)

- 通过对数据合并与顺序扰动(shuffle)来检验排名的鲁棒性,避免"对战顺序"或短期噪声把系统推向错误结论

- 保留一组稳定的 reference 模型作为锚点:在模型池高速变化时,通过固定或半固定的参考模型来稳定评分尺度、校准新模型的冷启动,并减少整体 ranking 的漂移风险

需要强调的是:Elo/TrueSkill 的定位始终是 filter,而不是最终真理。它的价值在于用最低成本快速排除错误解,把更稀缺的评估与实验资源留给更有潜力的候选模型——而最终的上线与训练决策,会在后续的 conversation-level A/B 与 RM 闭环中被进一步验证与优化。在当前流量下,我们通常可以在数小时内通过十万级对比样本淘汰明显不匹配的候选模型,把稀缺的更重评估资源留给 top pool。

Elo/TrueSkill 收敛:早期波动,后期稳定

User-Level A/B Fails in High-Velocity AI Systems

在消费级 AI 产品中,传统基于 user-id 的 A/B 测试正在系统性失效,其根本原因并不在于统计方法,而在于评估单位选错了。

User 并不是大模型交互中的最小因果单元。

在经典互联网产品中,将 user 作为实验单位是合理的:同一个用户在实验周期内接触的是稳定的产品逻辑,行为变化可以被视为对某个功能或策略的响应。但在 Consumer AI 场景下,这一前提不再成立。用户与模型之间的交互是高度上下文相关、路径依赖且非线性的——同一个用户在不同对话中的行为,往往比不同用户在同一类对话中的行为差异更大。

真正承载"模型能力差异"的,不是用户本身,而是一次完整的对话过程(conversation)。

如果评估仍然以 user-id 为单位,那么模型差异会被用户自身的强噪声、使用习惯与历史偏好所淹没;实验结果既难以收敛,也无法解释,更无法用于快速决策。在实践中,我们反复观察到:当模型迭代频率提高、候选模型数量增多时,user-level A/B 测试往往在统计意义上"显著",但在产品指标上却毫无指导价值。

这并不是实验设计的问题,而是评估对象与决策目标之间发生了错位。

因此,我们将评估单位从 user 转移到 conversation。每一次完整对话被视为一个独立的评估样本,在该样本内,模型接管整个上下文生成过程,用户的所有行为反馈(继续、打断、重试、放弃、时长、深度等)被统一归因到该模型在该对话中的表现。在当前规模下,我们每天会产生千万级 conversation 样本,使得 conversation-level 的归因边界不仅更清晰,也更容易在短窗口内收敛。

这一转变带来了三个关键变化:

第一,因果归因变得清晰。模型对用户体验的影响不再被跨对话、跨时间稀释,而是被限制在一个明确的上下文边界内。

第二,实验收敛速度显著提升。由于 conversation 级别的样本噪声远低于 user 级别,模型之间的相对差异可以在更短时间窗口内被识别出来,这对于高频模型迭代至关重要。

第三,评估结果更贴近真实产品决策。产品并不关心"哪个模型在某个用户身上长期平均更好",而关心"在当前使用场景下,哪一个模型更可能让一次对话成功发生"。

需要强调的是,Conversation-level A/B 并不是对传统 A/B 的一种优化,而是一种评估范式的转移。它放弃了对用户长期行为的建模,换取了对单次交互质量的高分辨率判断。这种取舍并非免费,但在 Consumer AI 场景下,它更符合系统的真实目标函数。

在高并发、快速迭代的生产环境中,模型的成败并不是由"用户是否总体更喜欢它"决定的,而是由在多少次具体对话中,它被真实用户即时选择或放弃决定的。

需要明确的是,Conversation-level A/B 并不是一个在所有条件下都成立的评估方案。

首先,当对话的价值主要体现在跨会话的长期关系或情绪累积,而非单次对话内的即时体验时,conversation 作为评估单位可能会低估模型的真实影响。例如,在以陪伴感、角色一致性或长期互动粘性为核心目标的场景中,用户是否持续回访、是否形成稳定使用习惯,往往比单次对话中的即时反馈更重要。

在这类情况下,单次 conversation 内的行为信号(继续、停留、选择)依然是有价值的,但它们不足以完整刻画模型在更长时间尺度上的用户价值。

其次,当产品处于早期阶段、对话分布尚未稳定,或用户规模不足以支撑充分采样时,conversation-level 信号容易被极端样本主导。在这种情况下,过早依赖该评估方式,可能会放大短期噪声,而非真实偏好。

此外,conversation-level A/B 有意放弃了对用户长期行为一致性的建模。这一取舍换来了更快的收敛速度和更清晰的因果归因,但也意味着它并不适合回答诸如"某个用户是否会长期偏好某一模型"这类问题。

系统设计的前提是:在 Consumer AI 场景下,模型是否值得继续迭代,取决于它在大量具体对话中是否持续被用户即时选择。

因此,Conversation-level A/B 并不是传统 user-level A/B 的完全替代,而是一个针对高并发、快速迭代模型环境的专用评估原语。它牺牲了部分长期行为建模能力,换取了在真实生产系统中可持续运行的决策效率。

Turning User Behavior into a Learning Signal

如果评估只能告诉我们"哪个模型更好",却无法影响模型本身的演化,那么它终究只是一个事后解释系统,而不是生产系统的一部分。

在 Consumer AI 场景下,模型迭代的速度和频率决定了评估体系的价值上限。只有当评估信号能够被持续、稳定地回流到训练过程中,模型选择、模型优化与真实用户偏好之间,才会形成真正的闭环。

这条回流链路每天会沉淀亿级隐式标签与大量成对偏好样本,从而让 reward 信号具备可持续训练的密度与覆盖面。

这正是 RM(Reward Model)在整个系统中的角色。

与通用奖励模型不同,Emochi 的 RM 并不是从抽象偏好或人工标注出发,而是直接建立在真实用户行为之上。系统并不假设用户会显式告诉我们"什么是好模型",而是假设用户会通过行为不断暴露真实偏好。

这些行为信号包括但不限于:用户是否继续对话、下一轮 query 的长度、对模型回复的停留时长、显式的 like/dislike,以及在模型对战过程中的真实选择。这些信号在单次交互中可能是嘈杂的,但在规模化聚合后,它们被反复验证与长期留存和参与度高度相关。

关键在于,这些信号并不是被孤立使用的。RM 的作用,是将来自评估系统不同层级的用户反馈,统一映射到一个可学习的奖励空间中,使得模型训练能够直接对齐真实产品目标,而不是对齐某个静态的离线指标。

需要强调的是,RM 并不是一次性训练出来的模型,而是一个持续校准的系统。随着用户行为分布、产品形态和模型能力的变化,奖励信号本身也会发生漂移。系统的设计目标,并不是消除这种漂移,而是在漂移不可避免的前提下,保持奖励与真实用户价值之间的长期相关性。

当评估信号、模型决策和训练反馈被统一在同一条闭环中时,模型优化不再依赖离线假设,而是直接受到真实用户行为的持续约束。这使得整个系统能够在规模化运行中不断自我修正,而不是依赖周期性的人工校准。

在这个意义上,RM 并不是评估系统的附属模块,而是 consumer-scale online evaluation 成为"平台"的最后一块拼图:它让评估不再停留在选择层,而真正进入模型演化的动力层。

需要说明的是,这套闭环并不是从理论推导开始的。它是在 Emochi 的真实用户环境中,伴随模型规模、流量和产品复杂度的增长逐步成型的。在长期运行中,我们反复观察到:当评估决策真正交还给用户行为时,离线分数与核心业务指标之间的相关性会自然退居次要位置。

Trade-offs and Failure Modes

这套 scalable online feedback loop 并不是为了解决所有评估问题而设计的。它的目标非常具体,也因此做出了清晰的取舍。

首先,这套基础设施并不适用于所有阶段的产品。当产品规模尚小(例如 DAU < 50k)时,用户行为信号过于稀疏且噪声较大,难以支撑稳定的在线排序与决策。在这种情况下,human evaluation 或 offline 分析仍然可能是更高效的路径。但一旦产品跨过这一规模阈值,继续依赖 offline evaluation 就不再是"稳妥选择",而是一种滞后的系统设计。在真实用户环境中运行的 AI 系统,如果评估信号不来自真实用户行为,最终一定会与产品目标发生系统性偏移。

其次,这不是一套用于回答"模型在绝对意义上有多好"的评估体系。系统并不试图给出跨时间、跨场景、可复现的绝对分数,也不追求与传统 benchmark 的一一对齐。它关心的唯一问题,是在当前用户、当前分布、当前产品形态下,哪些模型更值得被继续放量和演化。

再次,这套系统并不假设用户反馈是干净、稳定或可解释的。相反,它从一开始就接受现实约束:用户行为是有噪声的,偏好是会漂移的,产品形态本身也在持续变化。系统设计的目标不是消除这些不确定性,而是在不确定性不可避免的前提下,持续降低决策风险。

最后,这不是一个"一次性评估"的解决方案。它无法在模型尚未进入真实使用场景之前给出确定结论,也无法替代研究阶段的离线分析。它存在的前提,是模型已经被部署、已经被真实用户使用,并且评估本身需要成为产品和训练流程的一部分。

正因为这些边界的存在,这套系统才能在 Consumer AI 的真实规模下长期运行。它放弃了对"静态真理"的追求,换取了对"持续决策"的可靠支持;放弃了对完美评估的幻想,换取了一个可以不断自我修正的生产级平台。

这正是我们所构建的:

不是一个评估工具,而是一条能够伴随模型与产品共同演化的反馈基础设施。